Presenting Science in Publications

Manuscripts that address a relevant question and present a clear message based on original and new results,

written in the correct format and clear English, will be published, but not always in your favorite journal.

1. Why do scientists publish?

2. Measures for prestige: H-index and Impact Factor

3. The basic principle: a clear message for the readers

4. The elements of scientific writing

5. Stages in writing a paper

6. Ethical obligations of authors

7. The editorial process

8. Promote your work

9. Conclusion

1. Why do scientists publish?

That sounds like a silly question, isn’t it? Maybe you are a young PhD student who just reached an exciting conclusion of your first successful research project. Of course you cannot wait to see your work published, preferably in a highly ranked journal that is widely read by your scientific community.

By publishing you share your important findings with scientists all over the world. At the same time you hope that you will become known for this success, and that it may help you to build a successful career. Maybe your university requires publications before you can submit your PhD thesis. Your supervisor will obviously be happy with the new insights gained, but he will also be happy that the research group can boast another good article on the publication list. Without scientific production it will be difficult to acquire funding for the research. The university wants to see publications to prove its status as an important research institute. And so on. Hence a successful publication is important in many aspects, and not only for its content per se.

An study by one of the largest scientific publishers, Elsevier, conducted in 2005 revealed that authors mention the dissemination of new results as the most important reason to publish, but factors such as furthering my career, maintain funding, gain recognition or establish precedence as expert on a topic were very important as well as the second motivation. The consequence is that authors and their institutions are not just satisfied to see their work in print, they also want to see it in a journal that has prestige in the particular field of the author, or rather even in the entire scientific community.

2. Measures for prestige: H-index and Impact Factor

The scientific community has relatively recently (i.e over the past 10-15 years) adopted two ‘quick and dirty’ indicators for standing in the field, namely the Hirsch-index (H-index) and the impact factor (IF). Neither of them is normalized, e.g. for age and experience of the author, or for size of the scientific domain, implying that great care should be taken to interpret what these indicators mean.

Both are based on citations, i.e. references to articles by other published articles in recognized journals (reports, patents, books, abstracts of conferences, lectures, websites, etc do not count). It is good to realize this limitation: parameters for the impact of scientific work are not based on usage, but solely on citations in scientific journals, which is not necessarily the same of course.

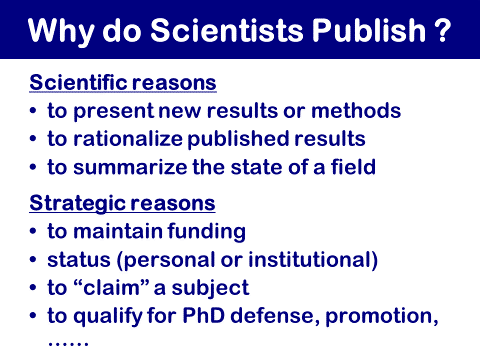

The Hirsch Index

The H-index is the number, H, of articles of an author (primary author or coauthor, there is no distinction in the roles that coauthors have played) that received at least H citations.

The way to determine someone’s H-index is to rank his publications in decreasing order of citations and se at which number in the list the number of citations is less, as graphically illustrated in the figure.

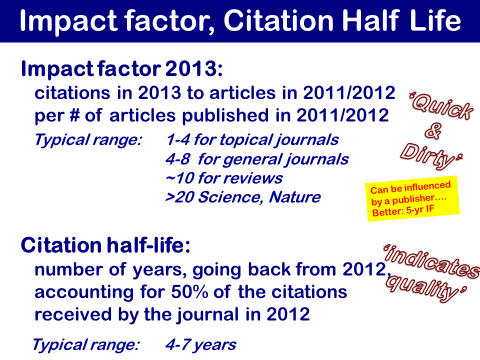

The impact factor

(and the citation half-life)

Prestige is based on citations, also for journals. Publishers want a quick indication of the impact a particular journal has in the field, and perspective authors want to know how well a certain journal is read, implying that their work has a better chance to be cited by others. Ironically enough, with all the search engines available these days it is less important where a paper is published, as readers seldom read through hard copies of journals anymore, but just search on line via key words or names, or use the references of articles they read as the source to find other literature.

The Impact Factor for a certain journal is the total number of citations in a year divided by the total number of articles published in the two previous years.

The citation half-life of a journal is the number of years going back from the present year in which 50% of all citations were made to articles in that journal.

- a publication often has some induction time before it starts to be known and cited. Some journals define an impact factor on a five year basis; interestingly, the values are not very much different from the usual 2-years values.

- the concept does not account for the size of a field. Another consequence of the definition is that as the scientific community grows, and tools for online search and for easily including references in manuscripts become more widespread, many impact factors tend to rise over the years.

- publishers can manipulate impact factors by artificially releasing issues in the beginning of the year, or to systematically publish a review in the first issue of a year. Creative readers can probably think up other ways of boosting short-term impact artificially.

In this sense the citation half-life is probably a more reliable indicator of quality and value, as a long half-life indicates that the journal publishes work that is of long lasting value. Hence typical archival journals can boast citation half-lives of 10 years or more. The same is true for review journals (the well established ones have both high impact factors and long citation half-lives).

In conclusion, prestige indicators such as H-indices and impact factors are easy to calculate numbers based on number of citations in recognized scientific journals, but one must be aware that they disguise a lot of detail, and that therefore they should be used with care.

3. The basic principles: a clear message for the readers

Scientific writing follows simple principles: the author has a clear message and he wants it to be read. The readers want a crystal clear and easy to digest message about an issue in which they are or may be interested. To this end articles follow a more-or-less standardized format, in which readers know where they can find what they want to know.

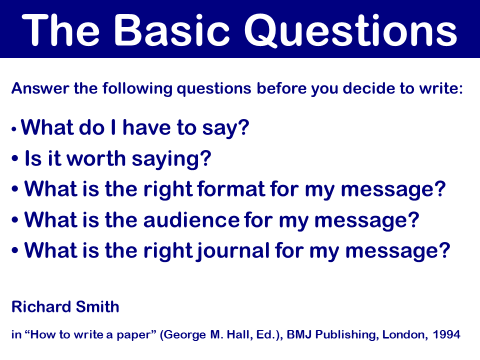

In his book “how to write a paper” Richard Smith gives the following advice to scientists who are considering to write a manuscript:

WANTED

- Originality

- Significant advances in the field

- Appropriate methods & conclusions

- Readability

- Studies that meet ethical standards

NOT WANTED

- Duplication (‘me too research’)

- Reports of no scientific interest

- Work out of date

- Inappropriate methods or conclusions

- Studies with insufficient data

Two other quotes in this respect:

“Just because it has not been done before is no justification for doing it now.”

– Peter Attiwill, Editor-in-Chief, Forest Ecology and Management

“What do I learn from it?”

– Roel Prins, Editor, Journal of Catalysis

If you are convinced that you have something important to publish, you can go ahead and start preparations, see chapter 5. But first it is good to review once again what scientific writing is about.

4. The elements of scientific writing

Be clear:

- Ordinary, short, familiar, non-technical terms are better than long, grand, unfamiliar, technical and abstract vocabulary.

- Avoid complicated sentences

- Realize that English is a foreign language for many authors and readers

Be objective:

- Unbiased, unemotional, truthful

- Give evidence to support your argument, while acknowledging any merit in other theories

- Separate results from interpretation

Be accurate:

- Facts need to be accurate and complete

- No vague, ambiguous, or misleading statements

- Carefully check all data and procedures you report

Be brief:

- efficient word usage

- concise Introduction

- brief Discussion

- effective illustrations, tables

A picture is usually equivalent to 250-400 printed words, however, it’s effect can be worth more than 1000 words .

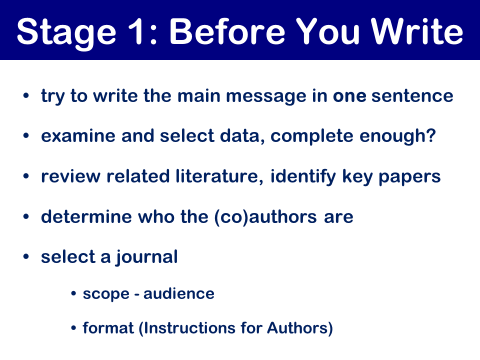

5. Stages in publishing a paper

Try to capture the essence of your paper in a single sentence:

This is your message.

“Ethylene polymerization on Cr/SiO2 catalysts occurs on atomically dispersed Cr2+ ions coordinated to SiO2 via two O-ions, as evidenced by in situ spectroscopic and microscopic evidence from a surface science / model catalyst approach.”

Next point on the agenda is to review again all related literature, and to identify the key papers that must be included in your manuscript. Be careful here, it is tempting to collect a long list of references from a service such as Scopus or the Web of Science, and to include all these in your manuscript. However be selective and try to mention only key papers that you have read (or have to read before you finish your manuscript).

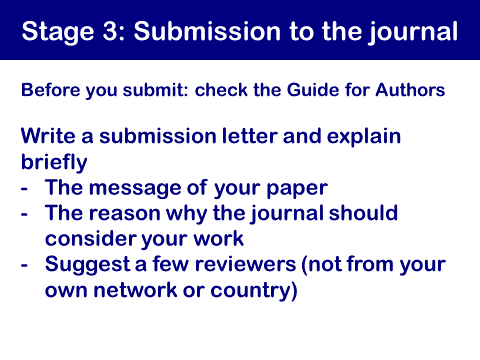

Finally, one has to select a journal. Many authors nowadays use the impact factor as a guide for selecting journals, or they simply select one of the well established journals of their field. Some will try to publish as high as possible in a more general journal of high reputation. If rejected, they go to the next one in the – sometimes only perceived – reputation list, until the paper gets accepted. Be aware, however, that most journals have a clearly defined scope, as described in the Guide for Authors, and that the first thing an editor will do is to judge whether your manuscript fits in.

Whatever journal you choose to submit your work to, make sure that you always read the Guide for Authors. Your manuscript must satisfy the requirements of for example layout, section lengths, nomenclature, number and type of figures and tables, and reference style. Do not annoy the editor by neglecting either the scope of the journal or its requirements for layout.

You may use your own list of references as a criterion to judge if your choice of journal makes sense. If your target journal, or related journals, do not appear in your list, you have probably made the wrong choice. Editors often also use this as a quick indicator for appropriateness.

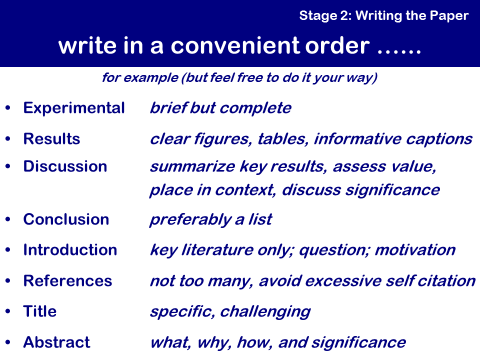

My recommendation is to write separate Results and Discussion Sections. In my view the main value of your paper is in the novel results that you are reporting. When documented properly, these results are of long lasting value. However, you will be interpreting the meaning of the results in the context of what is known now. It may well be that insights will change over time, and that your results will be used and interpreted in a different contextual framework than now. If your results are presented within an obsolete way of thinking, they will probably not be used anymore. Results, provided well presented, have eternal value; interpretations may be outdated tomorrow.

Writer’s block…

Although you have a clear idea about what needs to be written up, the right words don’t seem to come. Every sentence you write looks bad, inaccurate, poorly formulated, and it does not express what you want to say. Chances are big that you are suffering from writer’s block. It is a common phenomenon, particularly among less experienced authors.

The reason is that you are trying to do two things at the same time, which by nature don’t go along too well:

- Getting your ideas on paper is an act of creativity; it uses the right side of the brain, where intuition, creativity, appreciation for art and music reside.

- Getting g sentences in he proper form is a skill-based effort; it uses the left side of the brain, where analytic capabilities, logic, language, scientific and mathematical skills reside.

Combining creative ideas with technical skills to express an idea in a perfect sentence implies that you block one by the other. Hence, learn to apply the following principle:

Write first! – Then get it right!

In other words, write down what comes to mind, and don’t worry about language, sentence structure or spelling. Tomorrow you can revise your text and get it in proper shape.

Sections and elements

that usually get too little attention

-

Figures are extremely important and should be laid out with care. Often, however, the figures we see in publications are far from ideal. Please realise that the common software such as PowerPoint and Excel do NOT produce good figures at all.

-

Figure captions should be clear, informative and even attractive, such that the figure can be understood without reference to the text.

-

The same holds for tables, also these should be able to stand on their own.

-

Key words are important for abstracting services and for internet search machines, and can be essential for prospective readers to find your paper.

- References should be given in the proper format as requested by the journal; take care that all names are spelled correctly and make sure once more that you collected all the relevant references.

(a) Carefully designed texts on ordinates,

(b) Labels placed on spectra and curves,

and not in legends or captions,

(c) Labels that are understandable,

and not some type of secret code which only the author understands

– every author can make them

as long as he/she is willing to invest the time.

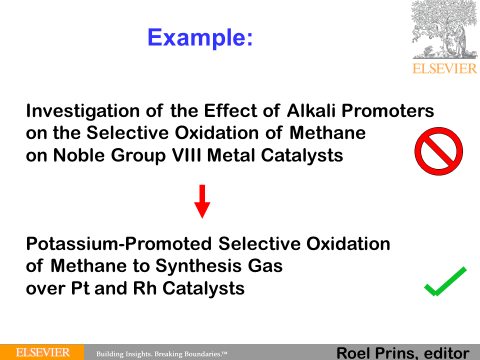

The title is the main attention getter; It should be brief, specific, attractive, and contain signal words that trigger attention. Don’t use constructions such as “A study into the useful effects of ….” which waste space and look boring.

Think back to the ‘message in a sentence’

– maybe a shortened version could serve as the title?

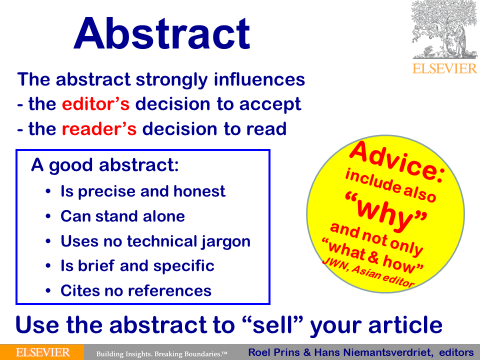

The Abstract is one of the most important sections of your paper. Editors may use it to judge whether your paper fits in the scope of the journal, and readers use is to decide if they will read it.

Use the abstract to convey your message

– and don’t use it as a verbose list of contents.

Finally, the paper is ready for submission:

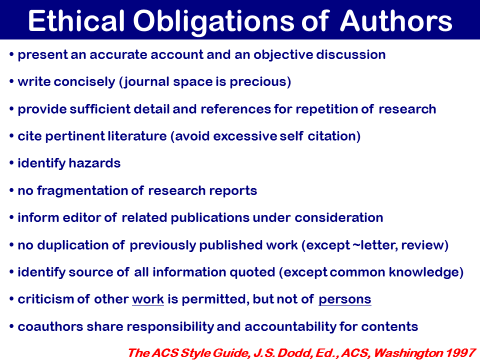

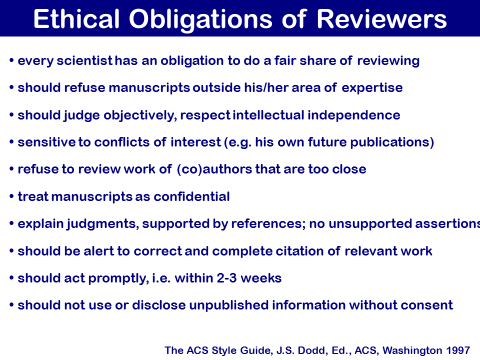

6. Ethical obligations of authors

Unfortunately, the world of scientific publishing has seen quite a few cases of misconduct recently, ranging from questionable practices such as duplicate publication, self plagiarism, or violations of good practice by not revealing complete sample information on materials or methods, to outright fraud, such as falsification and plagiarism. It is of the utmost importance that scientific leaders not only adhere strictly to ethical principles but also teach these to their students and coworkers. With respect to scientific articles the following list is a good summary of the main ethical principles for authors.

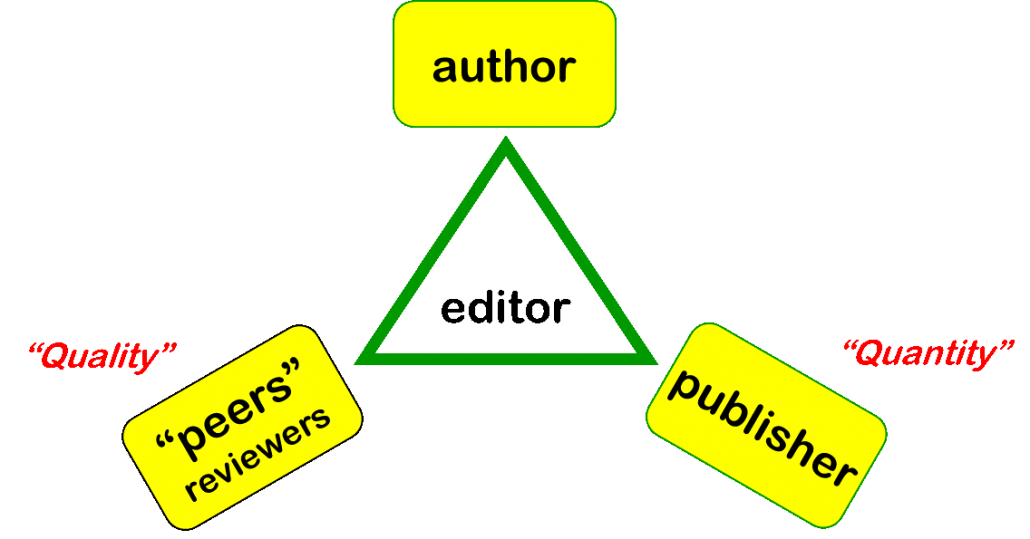

7. The Editorial Process

The paper is received by the editorial support office, who logs the paper in the system, checks if all documentation is complete and then forwards it to an editor. Hopefully he is an active scientist, but there are journals who handle this by a non specialist.

Anyways, the editor

- assesses the quality (incl. novelty) of a manuscript

- rejects poor or deficient manuscripts, or papers outside the scope of the journal

- invites reviewers to assess the manuscripts (usually 2-4),

who are asked to submit their report in a few weeks.

When all reviews are in, the Editor takes a decision on the basis of reports, which can be

- Acceptance (direct acceptance is rare)

- Revision, either minor or major

- Rejection

If reviewer recommendations conflict each other, the editor may invite additional reviewers, or go on his own judgement. If the decision is revision, the editor may choose to send a revised manuscript again to the same reviewers, or to take a decision on his own judgement, which is usually the case when requested changes were minor.

In case the decision is revision, the author should consider all comments carefully, and revise the paper where it is necessary. He should also write a reply to the reviewers, and indicate the actions he has taken, or explain why he did not change the paper. Authors can be slow in submitting revised papers, this is often a step that causes unnecessary delays in the publication process. A period of 2-3 weeks is acceptable, but in generally it is best to deal with revision immediately.

After submission of the revised paper, the editor may take a decision by himself, or send the paper out for review again. Let’s hope he decides to accept your work now.

In case the decision is rejection, then the authors should realise that they always have the right of rebuttal. A request hereto can be directed either to the handling editor, or to the editor in chief.

Rejection is of course a disappointing outcome, but it happens often, and even to well-established researchers and even to world-famous Nobel Prize winners.

The important point is to not take such decisions personally, but to evaluate honestly why the paper was rejected, and if addition of more results would enhance the chances of acceptance. Perhaps choosing another journal would be more appropriate.

8. Promote your work

Congratulations! Your paper has been published.

Now you have to ensure that it will be read and published. You should realise that the average number of citations is on the order of 1 per paper per year….. Hence make sure that people will know your work. You may send PDF reprints to selected colleagues in the field, present your work at conferences to promote it, and put an abstract and your best figures on the web, e.g. on social platforms such as Research Gate or LinkedIn. In any case, be aware that promotion of your work is important and that citations do not usually come automatically.

9. Conclusions

How do you get your paper accepted?

Focus on a clear message based on original results that address a relevant problem or question; stress why you did the work and what comes out; ensure that you write the paper in the proper format and correct English.

Never forget to check the Guide for Authors.